by Michael Dugan

The furniture business is undeniably challenging these days. Coping with a difficult economy as our industry has moved from producing to importing has not been easy. The furniture business has had its share of tough times, including about a dozen recessionary periods since the crash of 1929. This time though, it’s enough to make seasoned furniture men and women long for the good old days.

For this 140th year commemorative issue, the editorial staff of Furniture World thought it would be helpful to compare the current decade with those good old days, whenever they were. After considerable thought, we chose the mid 1960s and 1970s, the era when the Baby Boomers were entering their furniture buying years.

boomer generation

The entry of these yet to be named “Boomers” had been eagerly awaited. Writing in September 1955, Harry W. Schacter, President of Banner-Whitehill Corporation, wrote in Furniture World, “The furniture business is still in its horse and buggy days and must be brought into the second half of the Twentieth Century. The industry has not measured up in any appreciable way to the standards of modern distribution. It is the only form of retailing which has not kept in step with the times.” After taking more editorial space to criticize independent retail store owners, Mr. Schacter went on to identify coming opportunities.

“The other major reason for an urgent need for a change,” he said, “is the fact that in five years we should be on the threshold of the greatest home furnishings market in the history of the country. It is imperative that we, in the industry, be ready for it. Here's why: In 1940, there were approximately two million babies born in America. Then the war babies began to come in such droves that by 1954, 4,100,000 babies were born. In 14 years, the baby crop had doubled. By 1960, the 1940 war babies will be 20 years old and will begin setting up their homes. In the meantime, the age of marriage has fallen, home construction is booming, and family income is steadily rising. These are the three important factors in the health of any home furnishings market. If we are to be ready for the 1960 boom market, the time for action is now.”

Women’s roles were changing, although the industry didn’t seem to have a clue regarding the broader implications of that change. The population had become more affluent as well.

In a 1966 column on “Nearly Weds,” Richard E. Burow, the Second Vice President of the National Association of Furniture Manufacturers (precursor organization to the American Home Furnishing Alliance) said of this newest generation of furniture buyers, “Because of their age, this group has never experienced a major depression... mass unemployment ... a stock market crash... or a global war. For the most part, they have known both prosperity and parental permissiveness. As a result, we are meeting a new and different consumer.

“This is an acquisitive generation, used to spending.... Never have we had a more vital marketing opportunity.

“They are far more confident concerning matters of taste. Right or wrong, they want to make their own aesthetic decisions. Dissatisfaction and disapproval of the decor in their parents' homes is very evident. Many feel their parents' homes are cluttered or have a hodge-podge look which they intend to avoid.”

It was thought that an increasingly mobile population would also be a factor having a positive impact on furniture sales. “All of a sudden,” said Sherman Heazlitt, Vice President, Furniture Division Dolly Madison Industries, in a 1967 Furniture World article that encouraged the practice of group selling, also called correlated selling and integrated selling, “we're a nation of young people. Soon more than half our entire population will be 25 and under… It's become an age of mobility, too. People move from state to state, giving it no more thought—and with considerably less trepidation—than taking a cross town ‘El.’ Today, the average young man in business with a large corporation will statistically move about the country six different times before he's thirty years old!

“Remember when you married? If you were like most of us, hand-me-downs from parents, aunts, uncles, and grandma's attic comprised your entire first household furnishings. Not today. More likely it's, "First we'll get a car, then we'll buy new furniture." It's a juicy market for a furniture industry aspiring to boost its annual sales by three billion dollars in the next eight years, but we haven't made the most of it. As recently as February, FORTUNE Magazine pointed out that the Bureau of Labor statistics shows these people spend an average of only $281 a year on furniture, well below the cost of a color TV set. Clearly the (furniture) industry has a tremendous unexploited potential market."

This view was echoed later that year in a June article by William Pahlmann, F.A.I.D, who noted that, “Since 1945, a vast segment of the population of this country has moved from a subsistence income of roughly $3,000 per year to a middle-bracket income of $7,500 and up. According to Federal Reserve figures, approximately 80 per cent of the enormous middle-income group own a sizeable equity in their own homes. A typical family also owns a refrigerator, range, vacuum cleaner, automatic clothes washer and dryer, freezer, dishwasher, toaster, steam iron, electric clock, electric mixer, electric frying pan, electric coffee maker, television set, two radios and a phonograph. More than four million power lawn mowers are sold in this country annually.

“This rich market is ripe for the upgrading of interiors. They have the money. But many of them are bewildered by the range of selection and by lack of experience. I believe that in the immediate future a ‘total merchandise’ package plan for home interiors will have to be made available. Perhaps the word ‘total’ is extreme. I prefer a ‘basic’ package plan which could include the basic elements of a room—sofa, chairs, tables, rugs, lamps, accessories and so on for retail selling.”

Industry insiders felt that this large consumer demographic would buy furniture like mad. Well, the group never did live up to this expectation. Instead, a number of changes to the furniture buying process took place that had a major impact on retail channels of distribution for home furnishings.

THE WAY WE WERE

Back in the day when the Baby Boomers entered the market and put their mark on it, there were many more stores; department stores really emphasized furniture; sales reps played a bigger role; furniture insiders controlled manufacturing; and relationships counted more.

Those relationships were nurtured by visits to the field by factory owners and managers. Although manufacturers had many reasons to stay at headquarters, they could be refreshed and re-energized by store visits, even when they involved getting thrashed by irate customers. It was fun to be close to the retail action. Over the years, these visits kept producers from losing touch with the real world of retail.

By going into the field, manufacturing executives got hit with the truth, not the myth. There are few things more humbling than meeting the warehouse manager and reviewing the defects identified by his prep team. Then again, when handled professionally, these reviews made it possible to correct flaws and to clarify misunderstandings. Getting to know dealers in this close, friendly and generally lucrative business environment was also a gratifying experience.

EARLY AMERICAN WAYSIDE STORES

At one time, the corner stones of the independent dealer network, especially in the Northeast, were Wayside stores. These small to medium sized stores loved solid wood casegoods, wing sofas in nylon fabrics, cannonball beds, and Windsor chairs.

Haynes & Kane in Bennington,VT, Maple House in Westchester County, NY, and Cooper’s Maple Shoppe in Seattle, WA were among the leaders in this retail format that, in some ways, was the precursor of today’s life-style stores. They knew their customers well and really knew how to sell the solid wood story. Their carefully edited assortments and knowledgeable sales help were very appealing to consumers. In most cases, Pop typically ran the business, but Mom controlled what went on the floor. The preferred style for these companies was Early American Colonial and it enjoyed a big run in the 1960s.

The manufacturers that catered to these stores were family owned companies with old, multi-story plants producing furniture the old way. Some well known producers were H. T. Cushman, Hitchcock Chair, Sprague Carlton, Heywood Wakefield, Nichols & Stone, Moosehead, Bennington Pine, S. Bent, and the outliers, Ethan Allen and Pennsylvania House.

When the baby boomers came of age, they were not crazy about their parents’ “Ozzie and Harriet” furniture styles. By 1970, the Early American Colonial look was fading. In its place two distinct looks emerged, American Traditional and American Country. Cherry and pine replaced maple as the species of choice, and poster beds and Queen Anne chairs became top sellers. In upholstery, bullet-proof Herculon fabrics gave way to dressier covers, and sofas lost their wings.

Many retailers and manufacturers failed to adapt to the changes in consumer preferences and they simply faded from the scene. By the end of the decade, the Wayside stores had all but disappeared. A few, like Toms-Price in Chicago, were agile enough to migrate to new formats, but most quietly went out of business. Their retail format would become the basis for today’s “life-style” stores. Pottery Barn, Crate & Barrel, and Restoration Hardware are much more sophisticated, but not that far removed from their Wayside ancestors.

DEPARTMENT STORES

The primary drivers of furniture fashion trends, back in the day, were department stores, especially the upscale ones. They were exciting for manufacturers to deal with, able to write very big orders and certain to break the heart of even their best suppliers eventually. Bloomingdales was the fashion leading pacesetter. The furniture floor was huge and President Marvin Traub redefined the excitement of home furnishings, making it theatrical. Barbara D'Arcy's heart-stopping model rooms were redone every six months and re-opened with great fanfare like Broadway shows. Their costs were high and margins needed to be high as well. This led to the then unusual practice of importing furniture and sourcing that bypassed the mainstream. In hindsight, this signalled the beginning of huge shift away from domestic furniture production. At the time though, when Furniture World Magazine reported (December 1971) that furniture “imports have increased about 40 per cent, but they still remain equivalent to about 2 per cent of domestic shipments,” it was not a cause for concern.

Every major city had more than one department store and they all carried furniture: Jordan Marsh, Lord & Taylor, Macy’s, Gimbel’s, Abraham & Strauss, Strawbridge & Clothier, John Wanamaker’s, Joseph Horne, May Company, Halle Brothers, Higbee’s, Burdines, Lazarus, Bullock’s, Hudson’s, Marshall Field, Rich’s, Dayton's, Dillard’s, and the incomparable B. Altman. The buyers were superbly trained; the fashion coordinators created exciting displays; the tabloid mailers were powerful; they paid their bills on time: and they devoted gigantic display spaces to furniture, sometimes covering entire city blocks. For good measure, they also had branch stores in the suburbs with more space for furniture.

Because they carried related home goods, like bedding, lighting, accessories, rugs, and window treatments, they were able to present the total look to customers very effectively. More importantly, they were not afraid of the upper-end and they understood the importance of brand names.

Department stores were on the leading edge of fashion, however, they needed healthy margins to cover their overhead costs and their furniture margins were anything but healthy. Eventually, many of them began charging back for advertising expenses and taking unauthorized deductions. Sensible producers stopped selling them, especially after the infamous Campeau leveraged buyout venture bankrupted Federated and Bloomingdale’s. Closely related to the Department Stores were the Carriage Trade Emporiums… W&J Sloane, Payne’s, Barker Brothers, Breuner’s, J. B. VanSciver’s, and Cannel & Chafin among others. These throwbacks to the real old days loved quality goods and, in some cases, used Henredon as their starting line. Their superb interior design staffs ruled the roost. As the automobile replaced the horse and carriage and people moved to the suburbs, their appeal lessened. Some of these stores had great snob appeal. Having the Sloane’s truck pull up to your house was a real coup, but this was another turn-off to the Boomers. Eventually, burdened with high overhead costs, they were victimized by newer retail formats. They are nearly all gone now, and the industry's ability to make an impact on consumers with new product introductions has gone with them.

WAREHOUSE SHOWROOMS

And then came Levitz, not the easiest store to deal with, but boy, did they move goods. In 1963, Ralph and Leon Levitz opened their first ‘warehouse showroom’ in Allentown, PA, followed by one in Phoenix and another in Miami by 1965. The ideas they used were not new, but they had never been done so well or on such a grand scale.

Established furniture retailers in the 1980s looked at the ascendancy of North Carolina based ‘800#’ retailers that shipped nationally and did not pay sales tax, with dread. Later furniture retailers that sold over the internet were vigorously opposed. Likewise, warehouse showrooms were a threatening retail format in the early ‘70s.

Furniture World’s regular columnist, Clark Kelsey, looked at this phenomenon in a November 1970 article, titled, Caution: A Levitz Opening May Be Hazardous to Business. Mr. Kelsey observed that, “Between 50 and 60 years ago the traditional ‘furniture store’ resented the invasion of its field of operation by the department stores. Some 45 years ago, when so-called ‘mail order’ houses expanded from catalogs into retail store activity, there were even louder lamentations. During the past couple of decades, the ‘discount house’ has become an equally-feared bogey-man.

“Today… furniture stores would account for 77.7 per cent of annual sales in the nation, and department stores, 22.3 per cent, based on National Association of Furniture Manufacturers' 1968 estimates.

“The above history serves as a prelude to the account of a visit to Levitz Furniture, in Dallas, Texas. This is a new worry for the furniture merchant who has created desire for good things for the home, and another mercantile program rocking the boat for the dealer who believes that the furniture market was handed down to him by the heavens above.

“The Dallas Levitz was an early trial balloon for the discount hot-shots, whose securities on the American Stock Exchange have soared. Later editions have caused similar consternation in other cities, while 15 new municipalities are reported due for invasion.

“The Dallas entrance forces shoppers to walk through a cavernous! warehouse piled six-tiers-high with cartons imprinted with the brand names America knows in home goods. Fork trucks speed hither-and-yon. Three freight cars are being unloaded simultaneously on a siding. Entrance-way to the display floor is halfway through the cave - at the right. It carries this show-card: ‘This is NOT a retail store. Our prices do not include retail frills. Everything is priced in original factory containers, f.o.b. our dock. Services, such as delivery and set-up, are available at extra cost. Just like buying Wholesale!’

“A dozen aisles fan out on both sides of the broad central showroom corridor, displaying popular-priced furniture in schmaltzy settings. Goods are marked with two prices: The cartoned carry-away quotations seemed to average about a third less than the delivered, setup price. Gaudily appareled sales people were kept busy on a busy Saturday afternoon in October with traffic which resembled a super-market more than it did a furniture store.

“Back through the warehouse, turning left to a Texas-sized parking lot, trucks, rented U-Hauls and conventional cars, ranging from Volkswagens to Mercedes, were being loaded from dollies or fork-trucks by warehouse attendants and customers. Most loads were cartons, but some merchandise was free-standing and being roped down.”

Speaking of Levitz in an American Furniture Hall of Fame Interview, Lawrence Schnadig, founder of upholstered furniture manufacturer Schnadig Corp., said he, “refused to sell Levitz in the beginning of their growth because there was a good deal of antagonism to them on the part of our dealer list. However, their success was so fast and so great that we recognized we’d made a mistake; we went back and made an effort to develop their business, which we did.”

The Baby Boomers loved the idea of Levitz. Customers had to walk through a huge warehouse filled with furniture before they were treated to a large display of 250 model rooms. Only the hottest collections were selected, and everything was in stock for immediate delivery. Want more savings? Forget delivery and take it with you. What’s not to like? The stores had display, selection, savings, and instant gratification. The format was an immediate hit with consumers and the Levitz brothers took off and never looked back.

Levitz went public in 1968 and by 1970 were averaging $120 sales per square foot compared to an industry average of $26. In 1971, Levitz had 34 stores with sales of $183 million and profits of $9.2 million. The stock went through the roof and countless independent retailers went under.

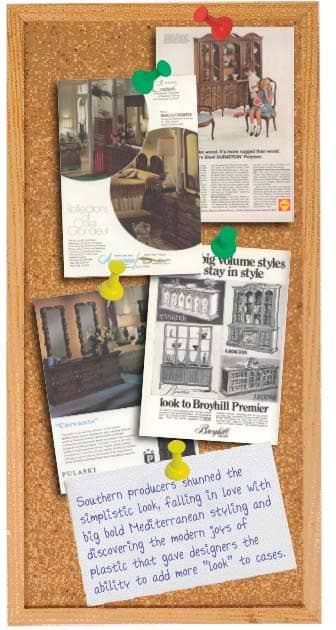

Feeding this behemoth with products to sell, were manufacturers like Bassett, Broyhill, Lea, Stanley, Burlington, Pulaski, and others. Far removed from the New England factories, these Southern producers shunned the simplistic looks and fell in love with big and bold Mediterranean styling. They preferred veneers to solids and discovered the modern joys of plastic that gave designers the ability to add more “look” to cases. They soon began designing for people who believed “too much was not enough.” The final product would sometimes end up with a combination of solids, veneers, prints, and plastic. The only way to tie all these together was by deploying some very clever finishing techniques. And they did. These faux finishes basically covered up the raw materials and used 20 to 30 finishing steps including equalizing stains, NGR stains, hand padding, spray padding, cow-tailing, spatter, and distressing. By the time they were done, the plastic looked like rare Honduran mahogany, or at least, some thought it did.

Plastics became big business for the furniture industry and were vigorously promoted. C.C. "Chuck" Redfern, Vice-President, Marketing Plastic Industries Inc., predicted in a March 1970 Furniture World issue that, “Much will be heard in the ‘70s about ‘plastic furniture for plastic's sake.’ This is in reference to the Italian influence of furniture molded in the most modern and avant-garde styles. Fiberglass, plexiglass, (acrylics) and polystyrenes will dominate the program, along with many expandable materials.”

By November 1971, Furniture World quoted a research study that forecast, “by the late 1970s, plastics will have replaced wood as the major material used in furniture production.”

Some of the collection names associated with this Baroque Era were Esperanto by Drexel Heritage, Andorra by Stanley, Monterey by Thomasville, Alvarado by Henredon, Marquesa by Sumter Cabinet, Conquero by United, Cervante by Pulaski and Boga Cierto by American Drew. On the upholstery side, the Warehouse Showrooms were perfectly geared to sell “motion” furniture. Recliners and sectionals that moved were hot, with La-Z-Boy, Action, Barcalounger, and Berkline leading the way with designs the interior designers detested, but the public loved.

But the bubble burst in 1972 when Ralph Levitz announced that the latest quarterly earnings would be disappointing. The furniture industry is fiercely competitive and rivals like Wickes and Sears had begun to put pressure on margins.

In a February 1973 forecast issue, Furniture World advised its readers, “1973 will see fewer openings of warehouse showrooms than 1972. The great majority of warehouse showroom operators are generating profits for their suppliers, landlords, and advertising media without generating profits for themselves. The key to profits of warehouse showrooms is no different than the key to profits in full-service stores... control of overhead. You cannot sell goods at low margins with 35 per cent overheads. Pendulum now swinging the other way regarding importance of full-service furniture stores. No one knows your operation better than you do. Stick with it, work at it, and reap the benefits. Ignore much inaccurate publicity in trade journals on warehouse showrooms. Don't be tempted to enter this type of business. All you will do is divide your strength. Stick with what you know and strive to be the best of your type of operation in your town.”

There were also some union problems and nasty SEC issues lurking around. On September 29th, Levitz stock dropped from $47 to $33 in 23 minutes before trading was suspended. Leon resigned, but Ralph stayed on. The company kept growing but the magic was gone. In 1974, Bob Elliott was brought in from Montgomery Wards as CEO and, by the end of the decade, Sales were $546.6 million and Profits were $20.6 million.

Elliott proved to be an astute merchant taking the company across the billion dollar sales level by 1995, but he also incurred a lot of debt in doing so as the company experienced buyouts, mergers, stock gyrations, and eventually bankruptcy.

Despite the dramatic highs and lows of Levitz, the Warehouse Showroom concept was a good one for the mass market and updated versions can be seen today. Mathis Brothers, remarkably, is able to capture the mass market and the upper end. Costco and Sam’s Club have only toyed with the category, but they do have market power.

GALLERIES

Before the Boomers arrived, the preferred display technique for furniture was called “rack ‘em and stack ‘em.” All dining rooms were lined up together in a sea of brown; all bedrooms were set up in similar format, sometimes with short rails on the beds to save space; and all upholstered goods were grouped similarly. Assuming the shopper was only interested in one room, he or she could easily make the selection. Of course, the means of display was mind-numbingly boring and frequently resulted in lost sales.

Somewhere along the line somebody, probably in a department store, had the audacity to put a bedspread on a bed (maybe even with pillows). Before long, some china showed up on a dining table and the race was on. Pretty soon, accessorized model rooms became popular, but resistance to this trend was strong in many quarters.

In some cases, retailers created contiguous displays of related products that happened to be from one manufacturer. One of the first to do so was Marshall Field that set up a Ranch Oak display in their State Street store and called it a ‘gallery.’ In Pittsburgh, the Joseph Horne Co. created a model house in the store using products from the Lewisburg Chair Factory and named it The Pennsylvania House.

Meanwhile, a rival named the Baumritter Company was aggressively pushing the gallery concept with a line of furniture and accessories called Ethan Allen. In 1972, co-owner Nat Ancell decided to go all the way and create franchised stores called Showcase Galleries.

Speaking of this time in an oral interview conducted by the American Furniture Hall of Fame, Nat Ancell said, “in the early years... 85 per cent of our distribution was through department stores with Ethan Allen having a gallery way back… And then as we developed, and our line broadened and we bought more factories and we went into the living room business, and the table business, and the occasional furniture business, and broadened the whole line… we found that department stores, particularly, could not handle our line because they wouldn’t give us the space we needed, and their salespeople didn’t know how to sell lamps and pictures and mirrors… The sales people... didn’t spend the time with consumers, and they didn’t know how to do it. And it became obvious to us that we would have to set up a different type of distribution and a different type of display and a different type of sales person and a different type of advertising and a different type of everything almost in order to reach the consumers with a decorating service, which is what we merchandised and marketed… We knew that in order to do that transition, we would have to have real Ethan Allen stores with plenty of space to show the products....”

In ten years there were 350 such stores and Ethan Allen had blown the doors of its rivals, with one exception.

With its survival at stake, Pennsylvania House fought back with an in-store Gallery program of its own. The results were impressive. As the program rolled out, sales grew fourfold, sales per dealer increased 15 times, sales per SKU went up eight times, and profits soared.

As word spread, dozens of gallery programs were attempted, but most failed, because resistance among independent furniture retailers proved to be hard to overcome. Sales representatives were wary of them and retailers were skeptical. Nevertheless, Drexel-Heritage, Thomasville, Broyhill, and Henredon had success with the idea.

The gallery concept made sense for certain manufacturers and retailers because consumers loved it. But for most, it was inappropriate. Necessary elements were a strong brand name, a cohesive product line, a sincere commitment, clean distribution, a great sales rep, and a close relationship based on trust.

And so, back in the decade of the ‘70s, much change occurred in the furniture business as the Baby Boomers entered their prime buying years. The Wayside stores performed admirably, but failed to adapt to the Darwinian selection process in play. Department stores gave home furnishings a substantial boost, but could not sustain the effort. Galleries made the shopping experience more enjoyable, but ultimately succumbed to dealer resistance. And Warehouse Showrooms filled up lots of homes before they lost their way.

The decade marked the end of the post World War II expansion of the American economy and it telegraphed the difficulties that lay ahead. In addition to discovering a new economic malady called “stagflation”, the industry had to cope with not one, but two hugely disruptive oil shortages and the prime rate hit 15 per cent and kept going.

The good old days were not easy, but it is generally accepted by industry people who lived through these times that they were fun. Those retailers that paid close attention to changing consumer shopping and buying patterns, and responded appropriately, prospered. Those who ignored the changing marketplace, and stuck with the old ways, did not.

About The Author: Michael Dugan is currently the Alex Lee Professor of Business at Lenoir Rhyne University where he served as the Chair of the Business School for five years. In 2004, he retired as President and CEO of Henredon Furniture Industries for 17 years. Earlier, he co-founded Jamestown Sterling Corporation and, in the 1970's he held a number of marketing and sales positions at Pennsylvania House. He recently published a book called "The Furniture Wars, How America Lost a $50 Billion Industry." Contact Michael Dugan care of Furniture World at mdugan@furninfo.com.

Excerpted From American Furniture Hall of Fame

Interview with David J. Brunn, Drexel Furniture Company.

“Macy Asked Us To Do A Coordinated Mediterranean Group.”

“Then in 1963 was my biggest success: Esperanto. This was designed by Jim Peed who joined our design studio. In Esperanto, we weren’t the first to do a Mediterranean group. As a matter of fact, one of my quotes is: ‘The trick in this business is the first to be second.” I think Century and one other company had done well in the Italian provincial styling. Ours were never copies. And the Mediterranean had been started by Thomasville, who had a group in that style, as well as Heritage. Esperanto made a tremendous impact in the industry. We got the single biggest order from any one store. A California store gave us an order for $50,000. Yes. One collection. We followed with another group in that same feeling called Palazzo, which was Macy-inspired. Macy asked us to do a coordinated group. They would merchandise the accessories and everything else that went with it. So we introduced that and that was

successful.”

Excerpted From American Furniture Hall of FameInterview with Patrick H. Norton, VP Sales Baumritter/ Ethan Allen & Sr. VP Sales & Marketing La-Z-Boy.

“We Opened Up 313 Ethan Allen Stores.”

“Well, I started reading things about this guy by the name of Ancell. He was doing things that were similar to what we had done in our stores... total room scenes... The first time that a (Baumritter) representative ever called on me to sell me what is now Ethan Allen, he wanted 100 square feet. Then he came back another time and he wanted 500 ft. Then the last time he called he said it’d take 3,000- 4,000 ft. I said, “You know you’ve got a lot of guts... So, I met this friend of mine and asked him if he had any connection with Baumritter. He said, ‘Yes. I can’t get you a job, but I can get you an interview.’ I said, ‘That’s all I can ask for.’

“I opened up the first Ethan Allen store… in Nashville, which was kind of a conversion. The first store to be built from ground up as an Ethan Allen store was Raleigh. The company had made the commitment. On Easter Monday (1964) we (Nat and I) met and we said we’re not going to have a modern division anymore… we’re going to have stores and we’re going to make it the best there is. Everybody said, ‘you’re crazy. People are not going to support one manufacturer. They’re not going to do all these things.’ We went through all that stuff. It was the right thing to do and I was in on the cutting edge of that program. When I left there in 1981, we had opened 313 of them and, I think, changed this industry for the better.”

Cold War Furnishings - Greetings, Mr. Khrushchev! From FURNITURE WORLD Magazine.

“Before a Soviet missile shot down an American U-2 spy plane in 1960, and the Cuban missile crisis made news in 1962, Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, met with President Dwight Eisenhower at Camp David. Mr. Khrushchev was addressed with patriotic bluster in the September 1959 issue of Furniture World. “Greetings and salutations, Mr. Khrushchev. On your visit here, see for yourself how America has attained the highest living standard in the world. If you care to examine the real reasons for our expanding economy, you must look beyond our booming industrial giants. Take the furniture industry for example. We’re now at full flood of prosperity….

“You’ll find furniture workers making $81.54 per week -- $91.09 if they are in the upholstering department. You’ll find three-quarters of factory sales made by ‘independent contractors’ carrying an average of three lines at an average commission of 5 per cent. Nik, you’ll find that a majority of furniture workers own their own homes and their own cars. Even air conditioning is booming for the ‘common man’ as well as the Rockefellers and the Hoffas. The five day week is general; leisure time is resulting in a natural tan as the national color…”

“Yes, Comrade Khrushchev, outside our kitchens and garages, you can perceive plenty of room for improvement in our average family's furnishings. Yet, we think that most of our people prefer their out-dated, 20 to 30 year old hand-me-downs to the ‘typical’ Russian home goods shown in your exhibition in New York City's Coliseum.

“If you are puzzled how some of our dealers can offer $79 mattresses - ‘half off’ - $39.50 - so are we, but... despite our problems, we see a new era ahead for the

furniture industry. Come back and see us any time, Mr. K. We're a big business done up in small packages, but we'll make more progress than your furniture commissars.... Yes, Nikita Khrushchev, we accept your challenge to compete in consumer products. And, when you return, be sure to bring plenty of vodka because the party will be on you, sir.”

FROM FURNITURE WORLD MAGAZINE:

Rise of Warehouse Showrooms

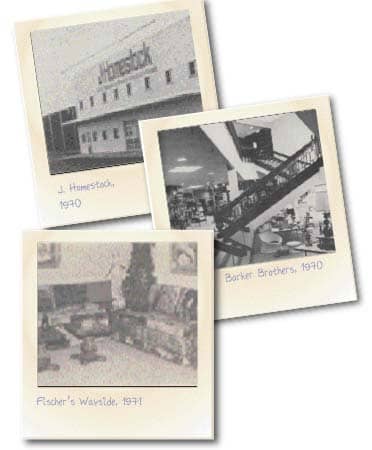

A number of furniture retailers emulated the warehouse showroom concept pioneered by Levitz in the early 1960s. In November 1970 Furniture World featured a new J. Homestock store in Dedham, Massachusetts that included, “a vast 171,000 square foot building with 330 room settings displayed on two floors.” By 1973 Furniture World advised readers, “The great majority of warehouse showroom operators are generating profits for their suppliers, landlords, and advertising media without generating profits for themselves.”

Advances In Store Design

Always known for innovative store design, Los Angeles-based Barker Brothers Furniture was featured in a 1970 issue of Furniture World. The article reported on a $490,000 renovation that featured the split level main entrance pictured and “an entirely new merchandising concept for Barkers: the display of total room groupings within individually partitioned settings to resemble a homelike atmosphere.”

Stores Fall By The... Wayside

When the baby boomers came of age, they were not crazy about their parents’ “Ozzie and Harriet” furniture styles. They turned away from Early American Wayside Stores whose retail format would become the basis of the “life-style” stores we have now. Fischer’s Wayside, Collegeville, PA was one of many similar stores featured editorially in Furniture World’s late 1960s and early 1970s issues. This article reported, “Service, of course, is highly emphasized and rightly so, for it is service: ‘before and after a sale’, for which Fisher's is well renown among its customers. A staff of accredited decorators is available to offer a prospective customer free decorating service.”

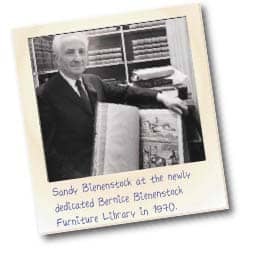

1970, The Furniture Library - A Dream Come True

In 1970, Furniture World and its regional sister publication Furniture South

established the Bernice Bienenstock Furniture Library. This educational foundation, reported a June 1970 issue, contains “five times more furniture books printed prior to 1800 than owned by any museum or library in America.

“The world's largest and most comprehensive collection of books pertaining to

furniture has found its home in a beautiful granite building in High Point, North Carolina. The Furniture Library was officially opened April 9.

“It brings to North Carolina those books published since 1640 and the only complete collection in America of Chippendale, Hepplewhite and Sheraton's original works, as well as those of other well known 18th Century cabinet makers.”

The volumes in the library, were collected over the course of a lifetime by Furniture World’s publisher and Furniture Hall of Fame Member, N.I. (Sandy) Bienenstock and his wife Bernice. “Within its handsome granite walls,” the article continued, “are

several separate workrooms, which will enable members of the industry to have quiet and individual work space. Schools will hold special classes in its main rooms.”

Today, the Bernice Bienenstock Furniture Library contains over 8,000 volumes on furniture design and provides more than 30 scholarships to students interested in home furnishings studies. Recently expanded and renovated, the Library also maintains a state of the art, climate controlled room to house its large rare furniture book collection and sells books in High Point and through www.furniturelibrary.com.

CLICK HERE to see FURNITURE WORLD Magazine's entire 140th year anniversary issue in "Flip Page" format.