YEARS AGO IN FURNITURE WORLD 1928-1934

Anniversary Issue -The Great Depression

by Melody Doering

Sixteen-year-old Evelyn Kidd, the pride of Spirit Lake, Iowa, won the National Home Improvement exhibit in her Four-H club’s contest at the International Livestock Exposition on December 4, 1928. “She displayed a color scheme of green, coral and ivory in decorating her own room, and exhibited five pieces of furnishings she had prepared at a total cost of only $8.55. In the prize-winning exhibit was a dressing table she made from two orange crates, and a modern electric lamp made from an old kerosene burner. She also had an old chair found in her grandfather’s barn, which she refinished. Candlesticks and pictures purchased at a five-and-ten-cent store complete the prize-winning room.”

Alas, there is no record in The Furniture World of Evelyn’s prize: The parsimonious ingenuity encouraged by the National Home Improvement contest certainly did not bode well for the furniture industry on the eve of the Great DepressionThe Furniture World of 1928, published weekly under an ever-changing logo, featured a charming mix of business and humor; the wisdom of sages complementing the opinions of the editors; serious discussions on matters of concern to the industry juxtaposed against chatty travel-diary letters from the globe-hopping Isse Koch, head of Isse Koch & Co., Inc; informational series on everything from splitting leather to growing moss, from mohair to curly hair, from veneers to proper sales techniques. Reporters throughout the magazine’s coverage area filed regular dispatches on the business and social activities in their regions.

There were classified ads of salesmen wanting lines to represent and companies wanting salesmen to represent their lines; ads to sell factories and equipment. A list of buildings – hotels, schools, theaters, clubs, churches, municipal buildings—that would be requiring new furniture was also a regular feature. A monthly accounting of failures of furniture manufacturers and retailers compared current numbers with those for the same month the previous year. On the brighter side, the magazine detailed the capitalization of new business ventures. And finally there was the Advertisers’ Index, a catalogue of 100 firms, give or take a few, that advertised within the issue.

The Boom Years

“When men take up an option, and then afterward seek for reasons for it, they must be contented with such as the absurdity of it will afford.”

– Sout

In mid-August, 1928, Theodore Price in his column in Furniture World, “The Business Barometer,” opined: “The ship of business is making good speed over a calm sea….” He did, however, caution that “bootleg money,” the credit loaned on call by institutions other than banks, was a hazard to “compel watchfulness.”

It does not appear that the financial activities of the late 1920s were of undue concern to those in the furniture industry. Furniture World presented the more pressing tensions among and between the major factions in the production of furniture. The designers, whose talents were focused on creating a durable commodity, were the misunderstood artistes, whose creativity was maligned by both manufacturers and retailers. The manufacturers, who fancied themselves “scientific,” trusted the designers to deliver sure-sellers and the retailers to order and promote those lines without resorting to piracy. The retailers, who dealt with a “fickle” public, were appealing to their customers’ sense of economy by seeking the highest discounts possible from their suppliers and then geared their advertising to price-point rather than quality. There was quite enough angst within the industry itself without fretting over the perilous economy.

“The Roaring 20s” conjures images of excess, not unlike the “bubbling 00s” of this century. In truth, what made it into the documents of record of the times often bore little resemblance to the lives of the common folk. By the end of the decade the cost of living had declined 21.5% since 1920 and per capita income had risen to $750 per year for non-farm workers. Yet, the buying power of the American public rested with those families who earned $5,000 and less. According to the US Statistical Abstract for 1901-1950, the average male worker earned 58¢ an hour, for a total of $28.25 a week. Women fared much less well at $17.62 a week.

The end of World War I in November, 1918, marked a watershed in consumer spending in several areas, but none more than furniture. For the two years after the war, expenditures in those types of goods associated with setting up new households rose dramatically, before falling to a level slightly above those of 1918. Jewelry (engagement rings?), clothing, meals eaten out, automobiles, and stationery (invitations and thank-you notes?) all rose, according to the Historical Statistics of the United States for 1900-1929. Expenditures on furniture rose 54% during that period, to $1,152,000,000. No other category of expense approached the furniture bubble. The wholesale price index for “house furnishing goods” from the same period rose a whopping 52%. How would it be possible to equal this explosive start to the decade? Even what would be considered healthy gains in business would be a disappointment in comparison to the post-war boom.

Indeed, the boom was followed by the recession of 1921-1922, which was felt universally. By 1923, however, recovery was in evidence across the board. Prices and consumption generally rose, buoyed by the easy availability of consumer credit, until 1926. That year was the one furniture men—and we’re not being politically incorrect here—looked to as the pinnacle in the industry, when all the elements of the industry were in harmony and profits were there for the taking. Perhaps 1926 became the utopian year because the government’s statistical index mean, last adjusted 13 years earlier, was again reset to 100, making comparisons painfully easy.

Art Moderne Tempest

“I do not think much of a man who is not wiser today than he was yesterday.” –Lincoln

There were no exhibitors from the American furniture industry at the Paris Exposition in 1925. Art Moderne was taking the world by storm, or so the designers said. William Millington, the general manager and designer of Furniture Shops in Grand Rapids toured the Exposition and reported in Furniture World in late 1928, “…what we are talking about and calling ‘moderne’ is probably the commencement of a new Renaissance… At first we could not see any beauty in it but gradually… some of us began to see the possibilities of developing something from this style which would be appropriate to the living conditions in America.”

This revolutionary art form, categorized by designers as belonging to the “skyscraper, television and trans-oceanic travel era” represented a decisive break from the Spanish and Italianate, over-stuffed, gee-gaw loaded furniture that graced a proper Victorian home. While the television era was yet to come, there being only one broadcast station in the US, times were changing. Fewer homes were “staffed” and when having to dust all the nooks and crannies of such ornate furniture fell to the homemaker herself, simplification was definitely in order. But was Art Moderne, the darling of the designers, the wave of the future?

Fred Rothermell of Almco Galleries wrote lofty screeds on the Art Moderne movement in Furniture World in 1928. “The world war cancelled our bondage to the past. In that struggle the titanic forces of the machine and the laboratory were dominant. A new age was born, a period of looking forward. Mass existence we have. Mass production must follow. With mass production there can be no servile traffic with the outworn. The elaborate symbols of an elaborate existence become painful caricatures when imitated by the machine.” He went on to castigate the manufacturing industry for having been “too long concerned with its function rather than the artistic quality of its result.” Stifled artists were being taken advantage of and current designs were the result of “an utter lack of courage….”

Meanwhile, the American Designer’s Gallery, under the leadership of Herman Rosse, was opening an exhibit of modern furniture to “show all America what is correct in the new art of decorating and furnishing.” The six-week exhibit would move from New York to the “ten most important cities of the country” to allow all those eager to modernize to learn the “proper standard.”

W. H. Wilson, vice president of the American Furniture Mart, Chicago, in Furniture World, August 1929 described Art Moderne as “slightly ribald—smart alecky.” He observed that many designers were trying too hard and ended up with results that were “often grotesque and freaky.” While New York and Hollywood had taken to the style, the country as a whole was not bound to adopt such radical departures of line and color. Art Moderne required its own background—a room designed specifically to showcase the furniture. It did not mix easily with the furniture of earlier periods.

The modernist movement, Wilson went on to report, did create a new awareness of color, which could be “scientifically” arranged. Although at least a third of furniture sold at that time was based on Colonial, Early American or Georgian periods, some more practical designers were modifying the moderne style to create furniture that, as an incremental step into the 20th century, could harmonize with diverse styles.

In the article, “Suggestions to Manufacturers and Buyers of Furniture,” in December 1928 Furniture World issue, author A. Dincin counsels that, “too often styles are created on the mere suggestion of designers; as a result, if a style fails to appeal to the consumer, the manufacturer has to kill off his stock at 20 to 25% loss, and the dealer remains loaded with merchandise that cannot be disposed of without serious loss. Why not go about creating styles with care, consult those who know the actual demand of the market, and who deal with facts, not with an artist’s fancies, and who can advise best?” This was a shot across the bow in the battle between the “scientific” side of the industry and the unquantifiable genius of design.

A more conciliatory approach was found seven pages later in that same December 6th issue of Furniture World, in a report of a speech by John Alcott, art advisor of Bird & Son, Inc., to the Southern Manufacturers Sales Conference. He predicted that within another quarter century manufacturers and retailers would develop a styling information bureau that would cover the trends of the public “as completely as the weather bureau traces temperature and humidity.” In other words, the left-brain, right-brain tension between ideas and execution could be successfully negotiated by having all parties join in pursuit of a similar goal.

Variety The Spice of Life

“Don’t insist on doing things the good old ways if a better way has been discovered.” –no attribution

New methods and products caused design change at the cusp of the depression. The use of helical springs reduced the bulk of upholstered furniture, allowing a more sleek line in accord with modern trends. DuPont introduced Pyralin, a plastic with mother-of-pearl effects, used to add color to bathroom furniture and dresser sets. Steel tube furniture, originally designed for the poor in Germany, was turned into a luxury item. The Ypsilanti Reed-Furniture Company introduced a line of steel tube chairs, the Flekrom English Lounging Chair, in 1929. In little more than a year, their design seems to have taken advantage of helical springs, resulting in a classic design suitable for the homes of today.

Kitchen furniture, topped with enamel, was offered in a profusion of colors. I-XL Furniture proclaimed, “We have leaned very strongly toward the green enamel, a light green, for this is a very soothing color but the sales seem to be increasing rapidly on the ivory and our gray, which is so much lighter than the average gray, being further brightened with the white panel centers and green stem and red petaled flowers, has been selling very well indeed.” One might assume that such an array would be cause for rejoicing; however, it ran afoul of the Federal Simplified Practice Experts who responded in a January 1929 issue of Furniture World to a call from business asking “whether something cannot be done to curb the tendency to apply color to autos, stoves and furniture....” The Simplified Practice Experts argued that having to match color when making repairs made color a material part of an article. A “mutually agreed upon set of colors” would cure the problem, curtail customer choice, and trim production costs.

The final word on color belongs to kitchen curmudgeon, H. F. Harbeck, president of the Challenge Refrigerator Company, who, when grousing about another topic entirely, went off message to declare: “The refrigerator is a refrigerator [note to the reader—the refrigerator was still an icebox for all but the wealthy] and nothing but a refrigerator. A piece of furniture is a house decoration. I know that some of the people tried to make a refrigerator a kitchen decoration, but it doesn’t seem to work very well. To my mind the best decoration for the kitchen is for the housewife herself to spend more time there and not to play so much at bridge parties.”

Those designers not boldly venturing into moderne, conservatively adapting period styles, or crafting a harmonious middle road, seemed to be dreaming up ways that furniture could do double or triple duty. The most common item for adaptation was the dining room table. With more people living in the smaller spaces of apartments and modest houses, a commodious table was instantly available with the flick of a lever. The spring loaded top would rise, freeing leaves hidden beneath. Once the leaves were pulled out, the top was locked back into place.

Daybeds, already popular at this time, were developed later in the Depression into sofa sleepers. In 1931 Simmons started a line of studio couches to enable families to deal with the challenge of doubled-up families. The recliner chair became popular, evolving from a chair and footstool into an all-in-one piece of furniture. The Sit-O-Sleep from Firmbilt Upholstery Company vied with the Ta-Bed by the United Table-Bed Company for creative design. The former, a variation on the recliner as shown in an ad in Furniture World, looks to provide comfortable repose. The Ta-Bed (not pictured), according to “Furniture Detective” Fred Taylor, was first made during World War I and was revived as a patriotic gesture during the Depression. The table was the size of a sideboard table with an unusually deep fascia, fronted with fake drawers. Upon lifting the fascia, which was hinged to the top, the springs and mattress were revealed and could be unfolded, as in a sleeper sofa. It was a bit of a climb into bed, as the bed assembly was rather high. The inside of the table top and folded-down fascia of the Ta-Bed did not invite comfortable reclining.

Radios at this time were often disguised in occasional tables. In a rare measure of inter-agency collaboration, the furniture manufacturers and the electronics industry cooperated to create radios with fine looking cases. Because radios had the flexibility to adapt to almost any design, this made an easy partnership. The Kiel Manufacturing Company, which later became A. A. Laun, solved the design dilemma with their “Golden Voiced Table.” The tuner was within the fascia panel and a peek underneath revealed the internal works with the speaker aimed at the floor. This model listed at $99.50 (without the tubes). Converting 1929 dollars to current rates, this home entertainment system would wholesale for $1,223.27 today. This shows how radical the art moderne designers were when they stated they were creating for a modern television age, when in reality, not every home had a radio, or even electricity!

While the above designs were both clever and utile, they pale in comparison to the combination piece offered by Peck & Hills Furniture Company in a January 1929 issue of Furniture World. Although it lacked a snappy name, it “combines in a single unit a radio cabinet, bookcase, writing desk, and a standard piano of artistic excellence, easily convertible from one to another.”

Industrial Angst A Vicious Cycle

“Forewarned, forearmed, to be prepared is half the victory. –Cervantes

Shortly after the halcyon year of 1926, the United States’ economy went into a deflationary period, causing a decline in housing starts. Somehow, manufacturers did not get the memo, and continued producing at their traditional rates. On the eve of the Depression, while many furniture companies claimed to have just had their best year yet, the industry as a whole bemoaned the slowdown, without knowing exactly what was wrong, much less how to remedy it.

The industry, long wary of organizations, began forming groups to address the problems of manufacturers. In an address to the first meeting of the National Association of Furniture Manufacturers in early October 1928 as reported in Furniture World, Alvin E. Dodd, of the American Management Association, declared that manufacturers must “adjust production to consumption, avoiding both over and under production. Over-production, necessarily, is under-consumption, that is, by stimulating consumption it is possible to absorb surplus production. But under-production may be avoided only by advance measurements of demand.”

Within those few lines lies a complex dilemma: how to measure demand in advance; how to manufacture just enough to go around; and how to stimulate consumption in the face of a deflationary economy.

Manufacturers, trusting in the new lines devised by their designers, often excoriated retailers for failing to hold up their part of the implicit bargain—they were not selling enough furniture. Retailers, caught between the public and the manufacturers, directed their ire in both directions. The customer, who was the ultimate determiner of success or failure for both concerns, was often viewed as an adversary rather than a partner in business. Furniture World genteelly moderated debates between the two giants. The arguments came and went in waves, first one side’s view for several weeks, and then the other’s. An insider could read between the lines of the gentlemanly disputes: names were not mentioned, and incidents cited were often of the nature of a cautionary tale. But when a business was caught engaging in truly egregious behavior, the editorial gloves come off and names were named, shady practices decried.

The customer, viewed in 1928 by one manufacturer on the pages of Furniture World as “fickle” and “ignorant,” had the power of the purse, and she was not buying. A more rational analysis of just who purchased furniture revealed that women were the primary customers. Those in higher income brackets, with a family income over $4,000 per year, tended to be most interested in period reproduction furniture.

From a manufacturing standpoint, this was a good line to be in. The industrialization of the furniture industry resulted in the greatest savings at the initial stages of construction, common to all pieces. The cleaner lines of Colonial and Early American furniture could be produced without skilled workers hand finishing carving details.

With little to be gained by antagonizing the customer, some enterprising retailers enlisted them to help set style trends by creating furniture exhibits open to the public. Robins & Robins of Philadelphia, in business only seven months in 1928, furnished a Colonial farmhouse in a suburb of the city. All furniture carried price tags and the house was staffed with salesmen to answer questions. After four months they had logged in 132,000 visitors and, presumably, gathered much information.

Many manufacturers called for creating style shows open to the public at or just prior to the markets, citing precedents of auto and radio shows. Furniture shows would feature sample rooms and be staffed to provide assistance. None of the furniture, however, would be priced. In 2010, an age of product testing, focus groups, and surveys, this seems like a win-win proposition: customer interest could provide a basis for buyers to place orders, allowing production in the correct amounts.

The suggestion was debated long and hard in issues of Furniture World, and finally attempted a few times in a less than enthusiastic manner. For an organization that prided itself as being scientific, it does not appear that the manufacturers took full advantage of a public willing to critique their product.

Borax Isn’t Just for Cleaning

“The labor of a day will not build virtuous habit on the ruins of an old and ruinous character.” –Buckminster

Advertising had become a bone of contention in the industry. The number of lines of furniture ads in June 1928 was only half what it had been the year before, as reported by Printer’s Ink and reprinted in September 1928 by Furniture World. Advertising professionals wrote articles on how to advertise more effectively, stressing that appealing to price only would not attract the kind of customers that would offer return business. A theme running through Furniture World in 1930, with the Depression being felt with a vengeance, was the evil of Borax advertising.

It is unclear how this mineral, used in the home as a laundry additive because of its ability to soften water, became associated with the furniture industry. None of the various folk etymologies advanced such as having come from coupons in Borax boxes redeemable for furniture, or from the Yiddish word borg meaning credit, stand up to scrutiny. David Schulman, writing in American Speech in 1985 convincingly rejects the previous explanations, as well as others, and cites that the term was in use before 1929 when H. L. Menken wrote “The Borax House.” The term was slang for anything that was cheap, and apparently was taken up by the furniture industry to refer to cheaply made goods, the retail establishments that sold them, the bait-and-switch methods of retailing, luring customers using easy credit, and advertising that was not truthful. Borax was all things bad.

The Better Business Bureau was the agency in charge of policing Borax advertising. In a rare instance of specific finger pointing, Furniture World named a New York city retailer that was charged with misleading advertising. Their ad copy showed two telegrams, one purportedly from the Grand Rapids Furniture Company offering the store bedroom suites at half price, and the other from the store accepting this bargain. Of course, there was no Grand Rapids Furniture Company, nor a ‘Lonsdale Model’ Bedroom Suite. The retailer claimed the use of the fictitious telegrams was “merely advertising propaganda.”

First Furnish Your Home

“No nation can be destroyed while it possesses a good home life.” –V. G. Holand

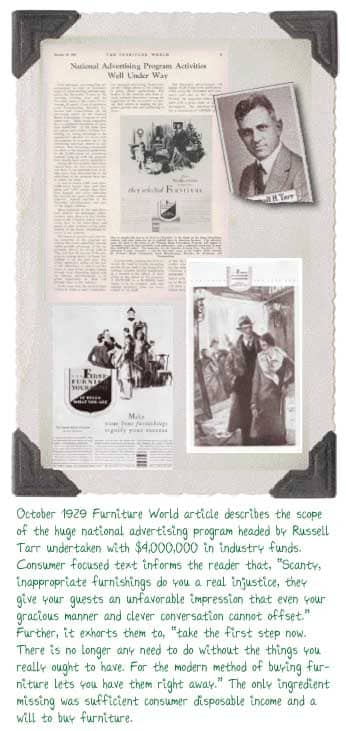

Late in the summer of 1928, the National Home Furnishing Campaign, headed by Russell H. Tarr and sponsored by the National Retail Furniture Association was launched. Its goal was to create product identification in an industry with hardly any, and to change the public’s view that furniture, as a durable good, needed replacement only every 17 years. At this time, only a few national brands were identifiable to the customer. One such line, Berkey & Gay, advertising in Good Housekeeping in April 1925, showed a woman primping at her vanity, with her maid looking on. The copy drew the comparison between how one feels in “new attire” and the youth one feels when changing furniture regularly. “For one thing she changed her furniture every three years—no matter how attractive… And her theory was sound, even though she carried it beyond the needs—the means—of most of us….” This up-scale ad, appealing to budgets between $600 and $6,000, was a clear point of reference for the Campaign.

Furniture World reported that the NHFC quickly raised the $4 million it required to launch the 4-year national media blitz. They aimed to “resell the Home to the American people. When we think together in terms of the Home and its glorification, when we influence the mind of the public to a similar way of thinking, then and then only will the greatest of our problems be solved.” Retail partners in the campaign were furnished with an array of support materials and were encouraged to display the logo of the organization to build brand identification.

The advertising generated by the National Home Furnishing Campaign, was to be of the highest quality, featuring classy art work, a logo to establish customer awareness of participating retailers, and story lines that played on a sure-fire emotion—guilt! The ads were to address the damage done by untrained admen. “The contact of the furniture industry with the public in the past has been made through local advertising, and much of it has been unattractive and unimpressive.

Price merchandising has beset the industry with many ills,” according to Fred Chapman of Ypsilanti Reed-Furniture Company.

The first ad previewed in Furniture World on September 29, 1929 and was slated to run in October in The Saturday Evening Post, American Weekly, Ladies’ Home Journal, Women’s Home Companion, Good Housekeeping, McCall’s, Delineator, and Cosmopolitan with an intended audience of 65% of American homes. This was supplemented with a direct mail campaign of 127 million pieces.

Absent the copy, the viewer cannot readily tell what is being advertised; a technique popular in today’s advertising. The reader is compelled to look at the artwork and read the copy to understand. The “First Furnish Your Home” crest was the emblem identifying participating retailers; all subsequent ads would carry the logo. The headline reads, “Make your home furnishings signify your success.” The text counseled, “Put your personality into your hospitality. Make your home truly reflect your business and social standing — a constant aid to advancement. Just as you judge others by appearance, you, too, are judged by the background of your home. What people say about your home furnishings in months to come, will rest upon what you do, NOW.”

How does one begin to unpack all the emotional baggage inherent in those few lines of copy? If you are successful, your furniture should reflect that; if you have not yet reached that level of success, your furniture ought to reflect your aspirations, which will then help you get ahead in business and society. Remember those catty remarks you made about the Jones’ furniture, well what do you think they are saying about you… and what are you going to do about it?

If the reader agrees that his image could use a makeover, he is reassured by the remainder of the ad that finding a participating store will solve all his home buying needs, and, furthermore, will provide support materials to help him get started on his path to success with a comfortable, stylish living room suite.

“Would you wear a gown as out of date as your DINING TABLE? You are judged by your furniture as well as your frock.” While the first ad targeted the male notion of success, the second, previewed in Furniture World for January 1930, shook an accusatory finger at the homemaker.

“Out-of-date furnishings betray you at every turn. No matter how bright and sparkling you may be… how charming and gracious a hostess, a home furnished with makeshifts and ‘hand-me-downs’ is a hopeless handicap.” In other words, unless your furniture is as modern as your gown, nothing you do will render you anything but a failure. Tell that to plucky 16 year-old Evelyn Kidd of Spirit Lake, Iowa!

Two subsequent ads were less manipulative—Beth was once more proud to entertain, and the bride and groom’s new home was all ready to receive them. Then parent guilt was played upon in the homey scene showing a family relaxing in a tastefully appointed living room. “It is HERE that memories are made; give your children the inspiration that comes from cheerful surroundings. Are you unknowingly penalizing their future by not providing the kind of surrounding they should have? Attractive, up-to-date home furnishings count tremendously in this formative period… Your youngsters deserve these advantages.” What conscientious parent could resist a sales pitch like that?

An article reprinted from The Rockford Furniture Herald at this time reported: “It is claimed that approximately $4,850,000,000 worth of furnishings in American homes are in such poor condition and so out-of-date as to make its replacement necessary. The cost of replacing it, $3,696,000,000, is about 24% lower than its original cost.” Perhaps such statistics influenced the most egregious of the “guilt” ads previewed in Furniture World—an ad which never even pictured furniture.

“FIGHT this competition of UNKNOWN PLACES.” In the shadowy foreground is a young couple: the woman appears discomfited as she strikes a pose, with her cigarette holder in one hand and the other on her hip; her companion looks down at her with longing. The scene behind them is oddly angled making it appear as if this couple was in danger of losing their footing. Another couple in the brightly lit background seems to be beckoning to them. The heroine in our drama is indeed about to misstep. Why? Because the home furnishings in her parents’ house did not allow her to “take pride in entertaining her first shy admirers at home.” When this ad ran in September 1930 in only The Saturday Evening Post and the American Weekly, there was probably more on the minds of the nine million anticipated readers than buying furniture to keep their daughters from the path of perdition.

Nation-wide Furniture Week

“Life is a long lesson in humility.” –Barrie

They said it couldn’t be done, but under Russell \Campaign organized a nation-wide style show to mark Furniture Week at the end of September 1930. Furniture World reported that in 350 cities across America, retailers, both subscribers and non-subscribers to the campaign, were poised to run promotions to boost the industry. The Hoover Administration was determined to study the problems of home ownership, and to that end, began the Better Homes Movement. Dr. Jules Klein, the Assistant Secretary of Commerce noted that “the home is ‘slipping,’ that it is scarcely able to compete with the ‘immature’ golf courses, the movies, the motoring facilities, and all the other vivid, fascinating devices that lure people to enjoyment elsewhere. We are told that the home has become a mere dormitory and cafeteria. But the more penetrating students of the situation believe that home-life is staging a come-back… that powerful scientific forces are working in that direction….”

In January 1931, Roscoe R. Rau, the Managing Director of the National Retailers’ Furniture Association commented on the popularity of “Buy Now” and “Bust the Buyer’s Strike” campaigns: “There is no buyers’ strike. It is a depression which takes from the laboring public the surplus which, when let loose and spent, makes GOOD TIMES. Until the underlying causes for bad times are eliminated, people will be working part time. We cannot expect them to buy. Artificial stimulation will never cure. It takes TIME. Time alone, as we see it, will bring back the prosperity we want.”

It was not until the end of March 1931, that some comment was made on the effectiveness of Tarr’s Furniture Week the previous fall. The editors of Furniture World stated: “Some furniture men with brains are planning a brawny campaign in the good old ‘homeopathic’ manner which they believe should do a 100 percent job in bringing the furniture industry out of its comatose state and putting it on a steady diet of success.” They added that an annual furniture and decorative style show was being planned for New York City to “teach the public that they can secure harmonious beauty at no greater cost than the ‘junk’ of which a great deal is now being offered… ‘Say it with flowers’ and its success was one of the reasons that a rather belated four year campaign which will cost the furniture industry $4,000,000 was launched and from what we have been able to learn the extensive annual style show plan in the individual retail stores was far from reaching the results expected. And don’t forget that, with the successful ‘say it with flowers’ advertising campaign, the florists continued and still continue to hold their annual show at Grand Central Palace, where thousands upon thousands pay admission.”

Undeterred, Tarr created a Home Styling contest in which each contestant was required to submit a diagram of a room of her house, showing its present furnishings, and then create an “ideal” arrangement. A letter was to accompany the entry form, stating what the new furniture would do for the family. Retail salesmen were encouraged to help guide entrants and were awarded cash prizes if their customer was a winner. In August 1931, the ten winners, one of whom was a man, had their photos printed in Furniture World, and began a 7,000 mile tour of homes around the United States. One of the purposes of the contest, besides providing publicity at each stop, was to get a sense of the tastes of the average furniture prospect. Finally an effort was being made to get the opinion of the public.

The National Home Furnishing Campaign then disappeared from the pages of Furniture World. Their innovative approach represented a collaboration of the various factions in the industry. Unfortunately they were battling economic forces greater than a mere “buyers’ strike,” as well as chronic industry-wide problems, rather than trying to retrench for the duration.

Retailers vs. Manufacturers

“When faith is lost, when honor dies, the man is dead.” –Whittier

Retailers, who were the essential link between the manufacturer and the customer, were often criticized by the manufacturers for not creating a demand for furniture. When the designers’ best efforts were not what the public wanted, how could the stores be blamed? An unknown author, writing in Furniture World in 1934, explained the retailers challenge: “…many times we do ¾ of our business on any item in only three price lines. The other 25 percent is too often done on 20-25 lines. But we try to carry as much money invested in each of the 20 poor ones as we do in each of the three best prices. Unless we have good luck we will find ourselves overbought and as a result will have to starve the three good prices until we are able to dispose of the surplus stock in the other twenty. In doing this we lose sales, profit and good will.”

Standard mark-ups between 75-150 percent of list price caused retailers to negotiate the biggest possible discounts from manufacturers in order to maximize their returns. For several years, in the face of slumping sales, retailers had advertised price-point above all other considerations. Furniture World reported that fully 85% of retailers’ ads played to price rather than design. Hyperbolic ads, claiming yet another “Sale of the Century,” did little to stimulate trade.

In the happy event a sale was in the offing, customers could pay in cash, with a charge, hold for future delivery, or on a monthly payment plan. Some accommodating stores even allowed customers to have an in-home trial period, abused by some, a “free furniture of the month” club! Some salesmen encouraged customers to purchase more than they wanted, and then return the excess. In July 1934 Furniture World reported that 1/3 of purchases in department stores were actually returned, artificially inflating the store’s sales figures. Sales staffs eager to move product, might “borax” a customer, getting her to buy more than intended with $1 down and easy payments of only $4 a week.

To aid retailers, Furniture World printed extensive how-to articles. For those who could not attend New York University evening classes in interior design, tuition from $19 - $29.50 per semester, there were detailed articles on how to set up credit lines for customers, how to create ads that would sell, successful sales techniques, and a series by Professor Elmer E. Ferris of NYU entitled, “Developing Sales Personality” that was easily a semester’s worth of lectures.

Some censure aimed at retailers was the result of disreputable practices. There is no way of determining if abuses increased during the Depression, but they were seen as particularly harmful to manufacturers in an already stressful climate. The excessive use of loss-leaders attracted customers, but were viewed as a “borax” maneuver. It was not unheard of for a store to place a healthy order with a manufacturer at one of the markets, and then as the furniture arrived, abruptly cancel the order on a flimsy pretext. Although not stated in Furniture World, it appears that many transactions were still handshake deals. Other retailers might order one suite of furniture, have the design copied by a pirate manufacturer, and sell the knock-offs at deep discounts.

Many articles appeared in Furniture World during 1930 decrying this piracy. By early 1931 the Vestal Bill, allowing for designs to be trademarked, was being debated in Congress and by retailers. While retailers feared it would create monopolies and drive up prices, manufacturers hoped that the streamlined trademark process of designs would offer protection. The bill was written into legislation and for the first time provided safeguards against the copying of stylistic features of furniture and clothing, in particular.

Economy-savvy Louis Meyers of Herrup Furniture Company in Hartford CT, writing an article titled, “Prosperity Must Live!” in the July 31st, 1930 issue of Furniture World, reported that “in an effort to aid in relieving the depression…Herrup’s has been offering its entire stock of merchandise at cost prices… in the hope that it will gain impetus and become nation-wide… If distributers cut their prices to the no-profit level, much of this money would again be put into circulation; wheels would turn again as new stocks were supplied, and there would be employment for workers.” Similarly, the magazine called for the employees of the 22,000 furniture stores and the 3,000 manufacturers to give a boost to the industry and show support for flagging sales by each refurnishing their homes. Unfortunately, 1930 was a bit too soon for folks to be investing in anything but the necessities.

Retailers regularly took manufacturers to task. In late 1929 Furniture World reported that a study of the views of 100 department and specialty stores on existing practices in the industry showed that the most prominent of these abuses were “delayed deliveries, faulty and improper packing, ‘open showrooms,’ failure to use discretion in selecting customers, selling direct to customers by manufacturers and wholesalers, faulty construction and use of inferior materials, misrepresentation, substitution, defective and inferior finish, and violation of exclusive agency agreements.”

Manufacturers vs. Retailers

“A great part of all mischief in the world arises from the fact that men do not sufficiently understand their own aims. They undertake to build a tower and spend no more labor on the foundation than would be necessary to build a hut.” –Goethe

Norman Freeman, in his article in Furniture World, December 1928, could hardly have won friends among either retailers or manufacturers by declaring: “Manufacturing is a scientific profession. Shop-keeping is trading and bartering, a game of opportunity. Manufacturing follows a charted road to a definite destination. Shop-keeping rides the waves, whichever way the wind blows… The [manufacturing] industry possesses too many smaller units, incapably organized, but primarily unintelligently directed….” While certainly tactless, he was onto something. The manufacturing of furniture was such a fragmented industry that it had no power to effect positive change for itself.

Far more prescient was Jas. H. Warburton, sales manager for the Marietta Chair Company, writing “Has the Furniture Industry Lost Its Vision?” in the following month’s magazine. He correctly diagnosed what ailed the manufacturing side: “It is highly probable that some furniture manufacturers are taking their low-prices-mass-production-cue from Henry Ford. It is stated that he figures on taking a loss on every car until the volume reaches a predetermined level… Speeding up production and slashing prices in order to move it and then trusting to luck that the demand will be such that there will be a profit, as a result of the lower cost of doing business is too much like buying fluctuating stocks on margin.” He cites the following figures: “If it is true that total furniture sales are approximately $1 billion a year and there are 25 million homes in the country, we are getting a measly $40 per year per home—about $6.80 less than the average man spends for his Lucky Strikes or Old Golds.”

Sales of furniture per family had been variously reported in Furniture World at $50 or $53 per year, a figure borne out by census statistics. In any case—far too low to sustain and expand the industry. (Warburton’s figure for cigarettes works out to about a pack-a-day habit at 15¢ a pack.)

Manufacturers were justly blamed on the pages of Furniture World for over-production, however, the nature of the industry made it inevitable. Those producing home furnishings were either batch producers, or custom/batch producers. Bulk production of furniture was the province of manufacturers of furniture whose design changed very little throughout the seasons – classroom desks or display cabinets offered few style choices and could be made efficiently. The preponderance of home furniture makers considered a cutting of 25 suites a huge order. More frequently the average order might be only 6 cuttings of a particular suite. Imagine the dilemma for a manufacturer upon the promise of a large order: once having secured the raw materials he must decide whether to cut and assemble the entire order; cut the entire order and assemble only part, having to keep track of the cut pieces; cut the entire order, fully finish part and leave the “white work” pieces unupholstered; cut and assemble only part of the order, reserving the raw materials for later finishing. Most companies were left with “distressed” stock at the end of the season and sold it to retailers at whatever they could get, hoping to recover costs.

The industry looked to Henry Ford for inspiration, not realizing that mass production was a whole different business model, for which the furniture industry was not yet prepared. Mass production required standardization and planned obsolescence: furniture, however, was an incredibly durable good (17 years) and came in countless varieties. So countless, in fact, that the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor was unable to calculate a wholesale price for “House Furnishing Goods.” Their annual reports footnoted that category: “Owing to frequent changes in patterns announced by manufacturers, prices of individual articles of furniture are only roughly comparable from year to year and are not shown.”

If One Dose Is Good, Four Will Be Better

“Employment and hardships prevent melancholy.” –Johnson

Back in the late 1800s a remedy intended to address the problem of overproduction was instituted. At twice-yearly markets manufacturers could display their wares, take orders from retailers and jobbers, and thereby produce just what was needed to fill demand. Traveling salesmen, with their catalogs, would reach those outlets not able to send representatives to the markets.

The remedy, however, became toxic, when more markets opened and new lines were introduced up to four times a year. Commenting on the numerous dates in an October 1928 issue of Furniture World, the aforementioned H. F. Harbeck, declared: “It is pretty hard to figure out just what effect the change in date of the Furniture Markets is going to have on trade. One thing I feel pretty well assured of and that is, the November date will never stick for Grand Rapids and Chicago. Even their January and July dates didn’t seem to fill the bill, so they inaugurated so-called Mid-Season Markets. That meant four markets a year instead of two.” In order to remain competitive, manufacturers were constantly obliged to interrupt their work on orders already in progress to retool and make newly-designed samples to display at the markets.

The following month Furniture World reported that Grand Rapids would have only two shows per year in May and November, but asked all exhibiters to leave their furniture through early January to accommodate those who could not attend in November. A Style-Show for the public at the February 1930 market in Chicago was organized to create interest in “furniture-consciousness.” By August 1930, calls were being made to reduce the number of markets to only one per year.

Although attendance remained relatively strong at all the markets, buying was not. A band of retailers made a blanket threat to manufacturers to curtail direct sales or they would lose out on future orders. Manufacturers would not quote prices to interested buyers until they could find out the prevailing rates of their competitors, and undercut where possible. There were more lookers at the Depression markets than actual buyers ready to commit to even a modest order.

In mid-1934, Furniture World editorialized on “Economical Market Planning.” “During the sixty-four years of Furniture World’s existence, we have found that it is practically impossible to eliminate all markets entirely. It has been tried time and time again, and although manufacturers will agree that it is a useless expense, they always go back to exhibiting merchandise because they find that the competitor is exhibiting.” They wisely called for an end to factionalism and appealed for unity within the industry for the good of the country.

Uncle Sam Steps In

“Pain is no evil unless it conquers us.” –Kinsley

What the furniture industry would not do for itself was done for it by the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933. The NIRA required industries to formulate business guidelines that would be universal to that industry. Retailers agreed on minimum wages for employees based on the size of the cities they were in. The agreement was hammered out by Roscoe Rau, his final act before retirement. Furniture World reported in July 1933 that “Under the code, adult male employees in cities of more than 1 million will be paid not less than $16 a week (48 hours); population 250,000 - 1 million, not less than $14; and not less than $12 in smaller cities. Women workers in the corresponding classes of cities will receive minimum pay of $12, $11, and $10, respectively.”

By August 1933 the Manufacturers’ Code was in place. Furniture World printed the conditions: the Code specified the definition of “cost;” limited hours to not more than an average of 44 per week; set wages by areas of the country and jobs; limited employment to those above 16; prohibited selling below cost; set terms of payment on invoices; outlawed piracy, secret rebates, misrepresentation, and commercial bribery; limited the building of new factories; offered to arbitrate contracts that needed to be renegotiated; and, permitted unions without coercion by business.

The furniture industry and the nation as a whole gradually began to emerge from the Depression by 1934. Progress was not always steady until the production demanded by the war effort stimulated the economy to a full recovery. Although the furniture industry in the pages of Furniture World bemoaned its sorry state, the cold light shed by statistics showed that they were generally no worse off than any other segment of industry. Curiously, the “Code,” which unified retailers and manufacturers, providing regulation in a fragmented industry, was discarded as quickly as it was legal to do so.

Furniture World in the Depression

“Be true to your word, your work and your friend.” –O’Reilly

Throughout this tempestuous period, Furniture World maintained its publishing schedule without fail. In January 1929, nine months before the crash of the stock market the editors said “…too many furniture men believe that our big and vital industry has ‘crashed on the rocks,’ or ‘gone to the dogs.’ It is about time to stop, sit up and educate ourselves to the fact that no one in this world gained advance with such pessimistic views.” So optimistic was their outlook, even in the darkest days of the Depression, that the reader does not get a true sense of the national economy. Better times were always “just around the corner”—even though the block had to be circled several times before those times were finally found.

Their Advertisers’ Index, a full double-columned page of more than 100 names in 1928, was reduced to a scant half page, doubled-spaced list that included hotels, Furniture World’s own ad page, and want ads. But they hung on.

In 1930 Furniture World consolidated with Furniture Buyer and Decorator, which was itself a combination of the American Cabinet Maker and Carpets, Wall Papers and Curtains. The same year, Furniture World began printing trademark registrations and provided free advance search for those wanting to register their new designs and patents. By 1931 the magazine also placed want ads without cost to individuals seeking employment. Furniture World’s Educational Institute provided semi-annual exhibits at the New York markets throughout the period.

Casualties of the Depression, sadly for this reader, were the pithy aphorisms printed above the opening editorials, and the corny humor, an example of which is directly below, that filled out columns in need of an extra inch. There is no record of who was responsible for these features, but from their diversity and sheer numbers, the research necessary might have provided full-time employment to someone.

“Mrs. A: Why did the cook you had with you so long leave? Mrs. B: She was in love with the iceman, and not knowing it, we installed an electric refrigerator.”

By 1935, the magazine’s style kept pace with the furniture it pictured on its pages: no longer a reflection of elaborate overstuffed Victorian designs, Furniture World took its place as a modern publication with sleek styling and snappy writing. It continued to provide a forum of instruction, information, and lively discussion as “The Mouthpiece of the Furniture Industry.”

Melody Doering researched and prepared the main text for the Great Depression segment in FURNITURE WORLD Magazine’s 140th year Anniversary issue. She is a Furniture World Contributing Editor, amateur historian and founder and president of Smart Ways 2 Learn, a company dedicated to the development of custom-designed, interactive educational resources. Her Flash-based games, designed for computer and SmartBoard use, are based on the recognition that learning through play is an effective model for both adults and children. Drawing from her varied experiences in music, entomology, and visual arts, her engaging games are used in schools, museums and businesses across the country.

Bibliography:

Carter, Susan B., et al, eds. Historical Statistics of the United States, Millennial Edition On Line. http://tiny.cc/78cGI

Dankert, C. E. “The Marketing of Furniture.” The Journal of Business of the University of Chicago, Vol. 4, No 1 (Jan., 1931), pp. 26-47.

Ettema, Michael J. “Technological Innovation and Design Economies in Furniture

Manufacture.” Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 16, No. 2/3 (Summer-Autumn, 1981), pp. 197-223.

Scranton, Philip. “Manufacturing Diversity: Production Systems, Markets, and an American

Consumer Society, 1870-1930.” Technology and Culture, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Jul., 1994), pp. 476-505.

Shulman, David. “Borax Reconsidered.” American Speech, Vol. 60, No. 3 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 283-285.

Taylor, Fred. “How to Be a Furniture Detective.” www.furnituredetective.com

United States Statistical Abstract 1901-1950.

Excerpted From “Shall Pillows Take Their Proper Place In The Furniture Store?” Salesmen Should Get Busy

October 19th, 1930

“This is the psychological time for Mr. Salesman to get busy. He should tell this woman, in a tactful way (he will need training on this), that her

cherished pillows are probably mixed or hen feathers, and may have been in daily use for three generations. Two

generations of forebears have died on them and three generations of babies have slept on them.... At any rate they are lumpy and uncomfortable. They were never as good as modern scientifically treated feathers.”

Award Posted In Mart Bombing

December 18th, 1930

“An award of $5,000 has been offered by the American furniture Mart for the arrest and conviction of the person or persons who placed a bomb in the building one week ago causing damage totalling $8,000.”

Haverty Furniture Starts Sales Drive

December 4th 1930

“ATLANTA. -- A 15-day drive to add 10,000 new accounts to the books of the Haverty Furniture Co., of this city, was started Saturday by the twenty-two stores of the organization... More than $1,500,000 worth of new merchandise, purchased for the 1931 winter season, was placed on sale in these establishments.”

Excerpted From American Furniture Hall of Fame

Interview with Elliott S. Wood, Founder, Heritage,

Henredon, Woodmark, Markwood & Founders Furniture.

“My Father Went Through Several Of These Tragic Experiences.”

“Prior to 1928, most of the floor covering manufacturers marketed their products through wholesale distributors, or jobbers. Jobbers were assigned a territory in which they were the exclusive distributor of the manufacturer’s products. There was a mark-up spread of about twenty percent. As the Depression wore on, some of the larger manufacturers, decided to eliminate their jobbers and sell direct, expecting that this plan would make them more competitive in the marketplace.

“The result was devastating for the jobber to learn that he was without a source of supply, that his exclusive resource had now become a competitor. The jobbers who survived this change were in a continuous scramble for replacing sources of supply. My father’s business went through several of these tragic experiences.

“Further devastation resulted from the closing by the Federal Government of our bank. What little money our business had left was put in escrow - any payout to be based on liquidation of the bank’s assets.

It was then in 1932 that I made the big decision that changed the direction of my life. I told my father that I no longer wanted to be in a business whereby your supplier had such complete control of your destiny, prescribing your territory, the inventory you were expected to carry, the volume you were expected to produce, the price you paid for your goods, and the price at which you were expected to sell it. That wasn’t the life to be for me.”

Excerpted From American Furniture Hall of Fame Interview with William P. Kemp, Sr., Founder, Kemp Furniture Industries.

“Sixty Hours A Week At Ten Cents An Hour.”

“In 1931 the plant was really in rather miserable condition. And it was just in the process of moving from a steam overhead control power to motor power.

“I was able to get together a group of small living room tables and made them. We sold them for 82 cents a piece. The jobber later sold them for a dollar.

“The object was, at that time, as a door opener, to get a group of tables to sell at a dollar and they were willing to sell them for a dollar as an advertising special. So that’s what we concentrated on. It took a little while, but we very soon got so we could make five or six hundred tables a day.

“People here in North Carolina were delighted to get any kind of job. And I really am ashamed to go over what we had to do. But everybody was.

There were so many people that were completely destitute. And most anything they could get was received with open arms. And our opening wage at that time was $1.25 a ten hour day, which is twelve and a half cents. There were also some at $1.00. They worked six days a week. That’s sixty hours a week at ten cents an hour, was $6.00 a week. But that was enough to keep them going, feed them and some of their family. Amazingly so. And at 82 cents a piece, if I had made a mistake in figuring my costs to a penny, I would go broke quick. And I think I was along with them at the time. But it worked out all right in the long run. But it took a while.”

Who Is Running This Country Anyhow?

W. Hume Logan, Logan Co., Inc., Chicago

January 9th, 1930

“Therefore, if there is any slump in business, it is altogether psychological.

Fifty years ago we might have been frightened into a panic, but surely in this enlightened age, with the above facts before us, the 95 per cent who have not speculated will not be such business cowards as to allow the pessimistic whines and groans of the 5 per cent to cause us to slow up appreciably in our program of progress..... Who is running this country anyhow -- the few speculators or the people who own, manage, produce and consume? Go to market with adequate costs in your pocket, courage in your heart, common sense in your head.”

What Is The Matter With The Furniture Business?

Irving H. Stern, Buyer and Designer Summerfield Co., Boston. January 16th, 1930

“The merchants who reduced their mark-up, unable at the same time to cut down their overhead, have gone into red figures for the past two years. Those who offered lower grades of merchandise are not only ruining their reputation and losing customers through the sale of unsatisfactory goods, but are obliged to increase their volume of business, as they must necessarily sell more pieces to maintain their

former volume. They must sell to more customers, which they are as a rule unable to accomplish.”

From An Open Letter To Furniture Manufacturers

C. Ludwig Baumann, President, Associated Furniture Dealers Of New York

January 8th, 1931

“We feel -- and we believe rightly -- that no manufacturer should expect to look to the legitimate dealer for business, and at the same time maintain an open showroom which makes possible the thriving or myriads of furniture bootleggers and embryo interior decorators, who have no warerooms, who make no investments in furniture and who have nothing to advance the interests of the industry as a whole...”

Excerpted From American Furniture Hall of Fame Interview with Lawrence K. Schnadig,

Founder, Schnadig Furniture

“Furniture Industry Hit Worse.”

“Subsequent to graduation, I did go to work for the Pullman Coach Company. The going rate for anybody at that time that could get a job at all was $35.00 a week. This was not a bad salary, because the money would buy something. You did not ask what pension plans they had or what insurance plans were available or the work hours or anything like that. The standard work week was five and a half days-- full days all of the week days and half a day on Saturday. However, once you got started you frequently worked seven days a week, because the economic conditions in the ‘30s declined very rapidly and the furniture business, being a consumer durable, was hit worse than any of the other industries.