YEARS AGO IN FURNITURE WORLD 1928-1934

Anniversary Issue -The Great Depression

by Melody Doering

Sixteen-year-old Evelyn Kidd, the pride of Spirit Lake, Iowa, won the National Home Improvement exhibit in her Four-H club’s contest at the International Livestock Exposition on December 4, 1928. “She displayed a color scheme of green, coral and ivory in decorating her own room, and exhibited five pieces of furnishings she had prepared at a total cost of only $8.55. In the prize-winning exhibit was a dressing table she made from two orange crates, and a modern electric lamp made from an old kerosene burner. She also had an old chair found in her grandfather’s barn, which she refinished. Candlesticks and pictures purchased at a five-and-ten-cent store complete the prize-winning room.”

Alas, there is no record in The Furniture World of Evelyn’s prize: The parsimonious ingenuity encouraged by the National Home Improvement contest certainly did not bode well for the furniture industry on the eve of the Great DepressionThe Furniture World of 1928, published weekly under an ever-changing logo, featured a charming mix of business and humor; the wisdom of sages complementing the opinions of the editors; serious discussions on matters of concern to the industry juxtaposed against chatty travel-diary letters from the globe-hopping Isse Koch, head of Isse Koch & Co., Inc; informational series on everything from splitting leather to growing moss, from mohair to curly hair, from veneers to proper sales techniques. Reporters throughout the magazine’s coverage area filed regular dispatches on the business and social activities in their regions.

There were classified ads of salesmen wanting lines to represent and companies wanting salesmen to represent their lines; ads to sell factories and equipment. A list of buildings – hotels, schools, theaters, clubs, churches, municipal buildings—that would be requiring new furniture was also a regular feature. A monthly accounting of failures of furniture manufacturers and retailers compared current numbers with those for the same month the previous year. On the brighter side, the magazine detailed the capitalization of new business ventures. And finally there was the Advertisers’ Index, a catalogue of 100 firms, give or take a few, that advertised within the issue.

The Boom Years

“When men take up an option, and then afterward seek for reasons for it, they must be contented with such as the absurdity of it will afford.”

– Sout

In mid-August, 1928, Theodore Price in his column in Furniture World, “The Business Barometer,” opined: “The ship of business is making good speed over a calm sea….” He did, however, caution that “bootleg money,” the credit loaned on call by institutions other than banks, was a hazard to “compel watchfulness.”

It does not appear that the financial activities of the late 1920s were of undue concern to those in the furniture industry. Furniture World presented the more pressing tensions among and between the major factions in the production of furniture. The designers, whose talents were focused on creating a durable commodity, were the misunderstood artistes, whose creativity was maligned by both manufacturers and retailers. The manufacturers, who fancied themselves “scientific,” trusted the designers to deliver sure-sellers and the retailers to order and promote those lines without resorting to piracy. The retailers, who dealt with a “fickle” public, were appealing to their customers’ sense of economy by seeking the highest discounts possible from their suppliers and then geared their advertising to price-point rather than quality. There was quite enough angst within the industry itself without fretting over the perilous economy.

“The Roaring 20s” conjures images of excess, not unlike the “bubbling 00s” of this century. In truth, what made it into the documents of record of the times often bore little resemblance to the lives of the common folk. By the end of the decade the cost of living had declined 21.5% since 1920 and per capita income had risen to $750 per year for non-farm workers. Yet, the buying power of the American public rested with those families who earned $5,000 and less. According to the US Statistical Abstract for 1901-1950, the average male worker earned 58¢ an hour, for a total of $28.25 a week. Women fared much less well at $17.62 a week.

The end of World War I in November, 1918, marked a watershed in consumer spending in several areas, but none more than furniture. For the two years after the war, expenditures in those types of goods associated with setting up new households rose dramatically, before falling to a level slightly above those of 1918. Jewelry (engagement rings?), clothing, meals eaten out, automobiles, and stationery (invitations and thank-you notes?) all rose, according to the Historical Statistics of the United States for 1900-1929. Expenditures on furniture rose 54% during that period, to $1,152,000,000. No other category of expense approached the furniture bubble. The wholesale price index for “house furnishing goods” from the same period rose a whopping 52%. How would it be possible to equal this explosive start to the decade? Even what would be considered healthy gains in business would be a disappointment in comparison to the post-war boom.

Indeed, the boom was followed by the recession of 1921-1922, which was felt universally. By 1923, however, recovery was in evidence across the board. Prices and consumption generally rose, buoyed by the easy availability of consumer credit, until 1926. That year was the one furniture men—and we’re not being politically incorrect here—looked to as the pinnacle in the industry, when all the elements of the industry were in harmony and profits were there for the taking. Perhaps 1926 became the utopian year because the government’s statistical index mean, last adjusted 13 years earlier, was again reset to 100, making comparisons painfully easy.

Art Moderne Tempest

“I do not think much of a man who is not wiser today than he was yesterday.” –Lincoln

There were no exhibitors from the American furniture industry at the Paris Exposition in 1925. Art Moderne was taking the world by storm, or so the designers said. William Millington, the general manager and designer of Furniture Shops in Grand Rapids toured the Exposition and reported in Furniture World in late 1928, “…what we are talking about and calling ‘moderne’ is probably the commencement of a new Renaissance… At first we could not see any beauty in it but gradually… some of us began to see the possibilities of developing something from this style which would be appropriate to the living conditions in America.”

This revolutionary art form, categorized by designers as belonging to the “skyscraper, television and trans-oceanic travel era” represented a decisive break from the Spanish and Italianate, over-stuffed, gee-gaw loaded furniture that graced a proper Victorian home. While the television era was yet to come, there being only one broadcast station in the US, times were changing. Fewer homes were “staffed” and when having to dust all the nooks and crannies of such ornate furniture fell to the homemaker herself, simplification was definitely in order. But was Art Moderne, the darling of the designers, the wave of the future?

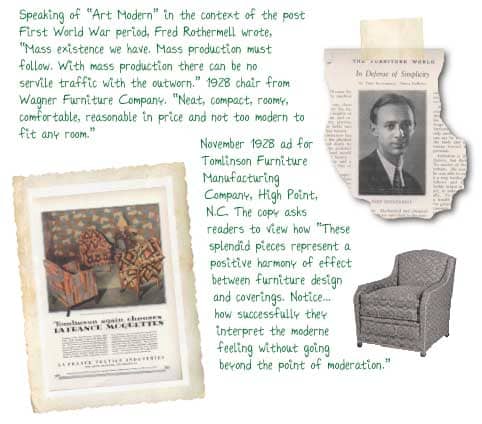

Fred Rothermell of Almco Galleries wrote lofty screeds on the Art Moderne movement in Furniture World in 1928. “The world war cancelled our bondage to the past. In that struggle the titanic forces of the machine and the laboratory were dominant. A new age was born, a period of looking forward. Mass existence we have. Mass production must follow. With mass production there can be no servile traffic with the outworn. The elaborate symbols of an elaborate existence become painful caricatures when imitated by the machine.” He went on to castigate the manufacturing industry for having been “too long concerned with its function rather than the artistic quality of its result.” Stifled artists were being taken advantage of and current designs were the result of “an utter lack of courage….”

Meanwhile, the American Designer’s Gallery, under the leadership of Herman Rosse, was opening an exhibit of modern furniture to “show all America what is correct in the new art of decorating and furnishing.” The six-week exhibit would move from New York to the “ten most important cities of the country” to allow all those eager to modernize to learn the “proper standard.”

W. H. Wilson, vice president of the American Furniture Mart, Chicago, in Furniture World, August 1929 described Art Moderne as “slightly ribald—smart alecky.” He observed that many designers were trying too hard and ended up with results that were “often grotesque and freaky.” While New York and Hollywood had taken to the style, the country as a whole was not bound to adopt such radical departures of line and color. Art Moderne required its own background—a room designed specifically to showcase the furniture. It did not mix easily with the furniture of earlier periods.

The modernist movement, Wilson went on to report, did create a new awareness of color, which could be “scientifically” arranged. Although at least a third of furniture sold at that time was based on Colonial, Early American or Georgian periods, some more practical designers were modifying the moderne style to create furniture that, as an incremental step into the 20th century, could harmonize with diverse styles.

In the article, “Suggestions to Manufacturers and Buyers of Furniture,” in December 1928 Furniture World issue, author A. Dincin counsels that, “too often styles are created on the mere suggestion of designers; as a result, if a style fails to appeal to the consumer, the manufacturer has to kill off his stock at 20 to 25% loss, and the dealer remains loaded with merchandise that cannot be disposed of without serious loss. Why not go about creating styles with care, consult those who know the actual demand of the market, and who deal with facts, not with an artist’s fancies, and who can advise best?” This was a shot across the bow in the battle between the “scientific” side of the industry and the unquantifiable genius of design.

A more conciliatory approach was found seven pages later in that same December 6th issue of Furniture World, in a report of a speech by John Alcott, art advisor of Bird & Son, Inc., to the Southern Manufacturers Sales Conference. He predicted that within another quarter century manufacturers and retailers would develop a styling information bureau that would cover the trends of the public “as completely as the weather bureau traces temperature and humidity.” In other words, the left-brain, right-brain tension between ideas and execution could be successfully negotiated by having all parties join in pursuit of a similar goal.

Variety The Spice of Life

“Don’t insist on doing things the good old ways if a better way has been discovered.” –no attribution

New methods and products caused design change at the cusp of the depression. The use of helical springs reduced the bulk of upholstered furniture, allowing a more sleek line in accord with modern trends. DuPont introduced Pyralin, a plastic with mother-of-pearl effects, used to add color to bathroom furniture and dresser sets. Steel tube furniture, originally designed for the poor in Germany, was turned into a luxury item. The Ypsilanti Reed-Furniture Company introduced a line of steel tube chairs, the Flekrom English Lounging Chair, in 1929. In little more than a year, their design seems to have taken advantage of helical springs, resulting in a classic design suitable for the homes of today.

Kitchen furniture, topped with enamel, was offered in a profusion of colors. I-XL Furniture proclaimed, “We have leaned very strongly toward the green enamel, a light green, for this is a very soothing color but the sales seem to be increasing rapidly on the ivory and our gray, which is so much lighter than the average gray, being further brightened with the white panel centers and green stem and red petaled flowers, has been selling very well indeed.” One might assume that such an array would be cause for rejoicing; however, it ran afoul of the Federal Simplified Practice Experts who responded in a January 1929 issue of Furniture World to a call from business asking “whether something cannot be done to curb the tendency to apply color to autos, stoves and furniture....” The Simplified Practice Experts argued that having to match color when making repairs made color a material part of an article. A “mutually agreed upon set of colors” would cure the problem, curtail customer choice, and trim production costs.

The final word on color belongs to kitchen curmudgeon, H. F. Harbeck, president of the Challenge Refrigerator Company, who, when grousing about another topic entirely, went off message to declare: “The refrigerator is a refrigerator [note to the reader—the refrigerator was still an icebox for all but the wealthy] and nothing but a refrigerator. A piece of furniture is a house decoration. I know that some of the people tried to make a refrigerator a kitchen decoration, but it doesn’t seem to work very well. To my mind...

CLICK HERE to read the rest of this article by Melody Dorival from the 140th year anniversary issue.