There are a lot of books out there that show you how to repair furniture. Tons of them, in fact. Most of them are very good, with instructions on how to repair well-made furniture built largely from solids, and give advice on white rings, iron stains and loose joints. But how does this help us, in an industry dominated by imports built from particleboard and resin? Repairing these products requires a special way of thinking, and for the first time, I’m laying out several of my proven techniques. They may sound easier than they really are, and in some cases they are easy, but as the saying goes, practice makes perfect.

Let’s discuss how furniture is made today. Solids are virtually a thing of the past, with the possible exception being trim pieces like crowns and base mouldings. Panels are made by laminating both sides of a piece of MDF (medium-density fiberboard) or particleboard with veneer: Nice wood on one side, cheap on the other. Obviously, the cheap side faces the interior of the cabinet. (Open pieces like wall units and armoires have nice wood on the inside as well.) This may sound like a cheap way to make wood panels, but the fact is, this system produces an inexpensive, strong working material that won’t cup, warp or split like solid wood. It also allows the manufacturer to carefully choose how the finished product will look, permitting inlays and designs.

Particleboard is made of sawdust and glue. Intact, it is strong and durable. Crushed or broken, it is like coffee grounds. For example, break a piece of cherry in half and try to flake away the split ends: You can’t. Real wood is held together by very strong carbon bonds. These bonds account for the loud noise heard when wood is broken into two pieces. Particleboard is strong on its surfaces, but once snapped or crushed, it is very easy to get the particles to come loose. Even blowing compressed air on the rough ends can loosen the individual sawdust particles, making repair very challenging.

Trim pieces are typically solid wood, but many manufacturers are discovering that they can save a lot of money by making these parts from resin or polymers like plastic. For example, consider what it takes to make trim. First, the wood must be rough milled, then finish milled. A shaper, which is a very expensive machine fitted with custom-made blades assembled in a stack, must be used to rout the trim (the finished shape is called a profile). The blades must be sharpened frequently, especially when milling hardwoods, or the trim will be rough and the machine may kick back, causing depressions in the wood. But casting with resins, however, is virtually flawless. The resin is poured into a mold and crudely reinforced (if you’re lucky) with fiberglass. Some trim is extruded, much like making pasta. Sections are simply cut off and finished. The molds are elaborate, too, etched to simulate wood grain and even knots.

So how are you supposed to fix this stuff? Here are some techniques that I use on a daily basis to restore damaged furniture back to first quality. You’ll be very surprised to learn that the primary repair material is cyanoacrylate (CA) glue, also called superglue or hot glue. Don’t confuse “hot glue” with hot-melt glue: CA glue is called hot because it becomes very hot when it cures out. Always use activator with CA glue because it speeds up the set time dramatically, but be careful, if you’re spraying it near a finish, use the pump-type and not the aerosol-type.

Case Tops: Crushed Corners

This is the number one problem almost everywhere I go. You’ll be surprised to learn that they’re not that hard to repair! First, assess the damage. If the crushed area actually distorts or affects the very top of the panel (in other words, not just the edge) consider replacing the top unless you have the ability to strip and refinish. To begin with, we need to restore the corner back to its original profile. To do this, cut two pieces of scrap plywood, about 4” x 4”, and cover one face of each block with plastic tape. This keeps glue from sticking to it. One of the blocks will be placed on top of the crushed corner, the other below it. If you need to, cut a “V”-shaped notch out of the lower block to allow it to fit the profile of the case. We want to have as much clamping power as we can between the top block and the bottom block. Now, put the blocks in place and apply clamps. Don’t bother with squeeze clamps, they don’t torque down hard enough, use “C” clamps. Before the profile of the corner is back in shape, very gently squirt some thin viscosity CA glue on the crushed area. Don’t let it run all over! Particleboard is very porous, like a sponge, and the glue will actually be drawn into the particles by capillary action. This saturates the particles, so when the activator is sprayed on, the particles are “frozen” into shape. Now here’s the trick: Make sure you are only one or two clamp turns away from bringing the profile back to shape. The particles have to be a little loose to allow the fluid to be drawn in. You have about ten seconds to make the final clamping. Once the profile is back in shape, apply the activator and allow the repair to sit in the clamps for a minute or so. Remove the clamps, wipe off the excess activator, and rough sand the profile with 100-grit paper. Using a putty-type epoxy (I recommend the five-minute stick type epoxy putty), pack the corner until the profile is restored, but use a little more than necessary so the profile can be sanded down exactly the way it is supposed to be. For this, use a block and some 180-grit paper to smooth the cured putty. Be sure to sand the bottom of the corner as well, and avoid scratching the top surface. Rub the sanded area with a clear filler stick to pack all of the open pores with wax, and remove the excess by rubbing vigorously with a rag. This heats the wax and helps it disperse. Mask off the very top surface and the body of the case, and finish as usual.

Tear-out

When a glide in the bottom of a panel gets hung up on a crack in the floor, it will either slide out, or move sideways, taking a large section of particleboard with it. I call this tear-out. To repair these areas, lay the case in such a way that the torn-out area is parallel to the floor. You will need some plastic auto body filler. Blow the area with compressed air to remove any loose particles, and gently saturate the area with thin viscosity CA glue, to “freeze” the rest of the particles in place. The trick is to make a “dam” on the edge of the panel to allow you to pour or spread the body filler into the excavated area and fill it, again, proud of the surface. Use a thin piece of plywood covered in plastic tape to make the dam. When the filler cures, remove the dam and sand the patch flush with the panel face. If the torn-out area involves a corner, use something stronger like the putty-type epoxy, and consider reinforcing the corner with dowel rods embedded into the panel.

Hollow Mouldings

The problem with hollow parts is that when they crack or break, it is difficult to support anything in the void since you can’t get at the back of the repair. To accomplish this task, use an expanding foam insulation product like Great Stuff. Fill the void, and when the foam cures, cut it about a quarter-inch shy of the original profile. Fill the resulting area with epoxy putty or plastic body filler, and sand to the original profile.

Faux Graining

In a previous article I mentioned the benefits of using basecoats. A basecoat is a tinted, heavily-pigmented lacquer, usually in an aerosol can, that completely disguises the wood or repaired area. I use them all the time to block out my repairs, because they quickly make the spot look like the background color of the wood (example, dark cherry finishes usually start out a chestnut color). From here, I use a 1” chip brush and apply some extra dark walnut glaze, or whatever color the grain is, and either stipple it on the basecoated surface to simulate end grain or a ragged finish, or brush it on to simulate the long grain. After it dries, I topcoat it with sanding sealer, and add dye-based or pigmented toners to achieve the final overall color.

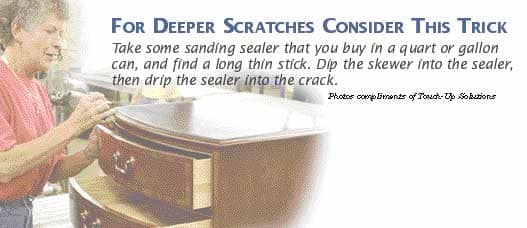

Scratched Tops

Here is another classic problem that daunts most inexperienced repair techs. Scratches have different degrees of difficulty. The easiest is the fingernail scratch. The hardest is the cross-grain, through-the-finish scratch. Fingernail scratches can usually be solved by spraying the top with the appropriate-sheen lacquer and then using a flow-out lacquer to level the overall finish. Deeper scratches that don’t penetrate the finish can be sanded out using 600-grit sandpaper and some cutting oil, sanding a little at a time until the depression becomes shallower; this is easiest to do on finishes that have some thickness to them, not the sparse ones. Be careful to check the sandpaper often for evidence of color, because this is an indication that you are cutting through the finish, which will require stripping and refinishing. If you have time, you can sand a little, wipe the surface with naphtha and spray on some sanding sealer to help fill the void. Sand again when the sealer fully cures. For scratches that are deeper still, consider this trick. Take some sanding sealer that you buy in a quart or gallon can, and find a long, thin stick, like a bamboo skewer. Dip the skewer into the sealer, then drip the sealer into the crack. Don’t overdo it. You want the drips to coalesce and stand proud of the surface. Allow the sealer to cure overnight, then wet-sand with 600-grit paper and cutting oil. The sealer acts like a burn-in without the risk of the repair becoming shiny when it is lacquered, and it is perfectly clear.

The way furniture is constructed is changing, and we all need to change the way we think about repairing it. A lot of techs are intimidated by what seem to be difficult repairs but they’re really only telling you two things: One, I am indeed intimidated, or two, I don’t wanna fix this. My advice is to ignore both pleas. Provide the techs you have with the right materials and tools (if you’re unsure, hire a consultant to help you set up the right configuration without guessing for yourself) and challenge them to at least try. They may tell you that trying takes time, and that it might not come out right. Everything takes time! The alternative is to continually send things to clearance, or order replacement parts, rather than provide the tech with an opportunity to grow and learn. I assure you, the former is much more expensive than the latter.