“I can’t sell those people because they’re different,” Larry exclaimed.

"I can’t sell those people. They’re different,” Larry told me in defeated tone, after failing to make a sale to a Hmong couple. Hmongs are just one of the many foreign-born customers who shop in the Minneapolis inner city store where Larry works.

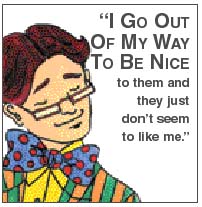

“What’s the problem,” I asked. “It’s like trying to walk through a stone wall,” he answered. “I go out of my way to be nice to them and they just don’t seem to like me. If they would only speak to me instead of giving me an innocuously enigmatic smile.”

Larry, in addition to being a self-educated man who devours books for the sheer joy of reading, is also a very personable fellow. He is neither arrogant nor xenophobic, and certainly has no noticeable racial bias. Most customers are immediately comfortable with him. He exudes a caring attitude that generally wins him instant rapport.

Further conversation revealed that having failed to establish rapport with some of his foreign-born customers, Larry had redoubled his efforts. It was obvious that he was going “out of his way” to try to relate to them.

It was this extra effort that had raised a “red flag” that ultimately resulted in their failure to buy. People don’t want to be treated differently. As important as our cultural differences are, they are not nearly as important as our common humanity. In that we are exactly the same.

People may speak another language, they may relate differently to the sales process and their body language may seem enigmatic to the average retail furniture salesperson.

But give some thought to why they fled their native land. Many came to North America to enjoy fundamental human rights, often passing through terrible ordeals. Their goals included freedom of speech and the pursuit of happiness. These are important rights, but from a sales perspective, there is another right that every sales person should keep in mind.

Michael P. Nichols mentions in his book, “The Lost Art of Listening,” that “All human beings yearn to be listened to.” The American Psychologist William James stated the similar observation that, “All people want to feel appreciated.”

Now Larry intuitively understood this fact. Realizing, that the Hmong couple mentioned earlier yearned to be listened to and wanted to feel appreciated, he went out of his way to be nice to them.

The problem was that his intent didn’t have the desired effect. His intent in going out of his way was good; but the effect in this case was just the opposite. That Hmong couple did not want to be appreciated for what they might some day become; they wanted to feel appreciated for what they already were. They sensed that he was not being himself, that he had to be different with them because he believed they were different

Within several weeks of having this realization, Larry witnessed a dramatic change in these “different” customers. Customers he had worked with started asking for him again and again. Larry began to feel as comfortable with his foreign-born customers as he did with his native-born customers. No, Larry didn’t take crash courses in related foreign cultures. Nor did he go out of his way to win foreign customers over. Larry simply was himself, and, of course, in Larry’s case that was bound to be effective. He went on to build the same kind of rapport he had always built with his other customers: by being kind, fair, and sincere. Together with those virtues he avoided the vice of condescension that destroys the possibility of every other virtue.

Condescension grows more vicious the more well-intentioned it is. Good intentions do not always lead to good effects.

Corporate trainer, educator and speaker Dr. Peter A. Marino has written extensively on sales training techniques and their furniture retailing applications. Questions on any aspect of sales education can be sent to FURNITURE WORLD at pmarino@furninfo.com.